One of my chief aims in macro photography has been to get closer to my subjects to highlight the extraordinary beauty and complexity of Australia’s invertebrate wildlife, but budget can play a big part in the gear one chooses. When I first started, it was just a fixed-lens camera with a macro setting and a bit of digital zoom, which was enhanced a little by a couple of screw-mount close-up lenses. When I upgraded to a Canon DSLR, I chose the EF 100mm f2.8 USM macro lens. This was a great leap forward in terms of image quality and detail, but there was still something missing.

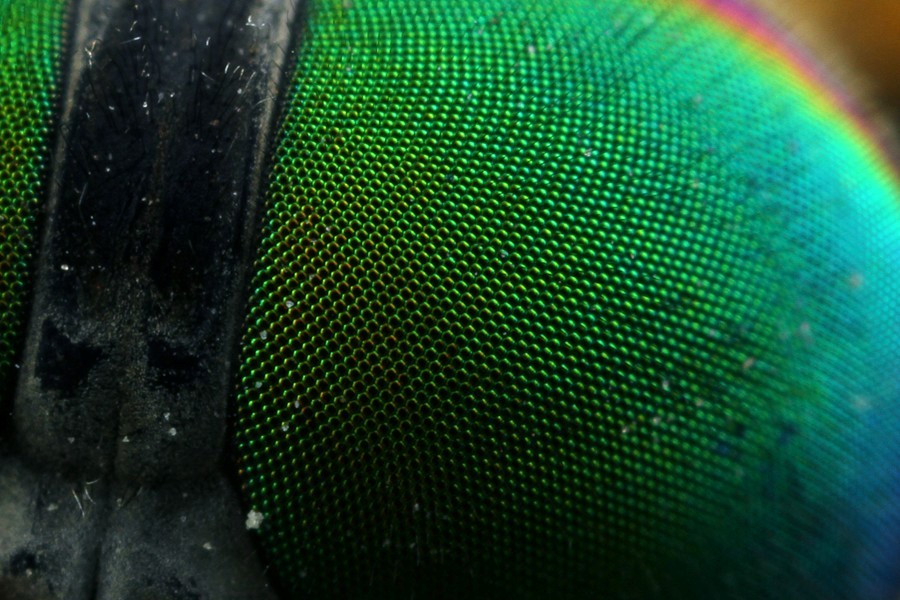

In August, 2013, I finally convinced myself to take the plunge and spend some hard-earned on a Canon MP-E 65mm macro lens. To be honest, this lens frightened me because I thought it was going to be very difficult to handle, but I have to say that it was the best risk I have ever taken as far as photography goes. This beast of a lens is purpose-built for macro photography and when the maximum focal distance is an insanely small 10cms (4 inches), it’s clearly not going to be much use for family snaps.

The lens offers a range of 1x to 5x magnification and at 5x the focal distance is reduced to a mere 1.5 inches. At either end of the scale, the amount of light that is let in isn’t much, so the flash becomes almost essential. And let’s throw in the fact that it is all manual focus, although you don’t actually focus the lens – you pick the magnification you want and then you physically move closer or further away until the subject is in focus. Oh, and let’s not forget that the depth-of-field is only a matter of millimetres or less, so the slightest movement will throw everything out of focus. You would think the whole concept of this lens is nuts, but it’s not as bad as it sounds.

Everyone has their own opinions on what’s best, but for me it’s about depth-of-field and light. I like to maximise the depth-of-field, so I usually shoot at f14. Coupled with an ISO of 250 and a flash speed of 1/250th of a second, this results in almost no natural light being let in, but there is a reason for that. When the flash is employed in these situations, it provides enough brief light to illuminate the subject and completely freeze the image. There is nothing worse than motion blur caused by camera shake or external influences such as the wind. Because the flash is so much closer to the subject, the spread of light is more even and I have far less trouble with specular highlights (the shiny patches that appear when the flash is reflected off a shiny object). Diffusers help in this regard as well, but I’ll cover that in another post.

Oh, and in case anyone is curious, all of my images are taken hand-held. That means NO tripod. Why? Because tripods are cumbersome objects that often make it difficult to get close enough to the subject, and besides, not many insects will sit around long enough while you mess around setting up the tripod in the right position and at the right height. If something steady is required, that’s what rocks and trees were invented for.

The downside of the MP-E is that some insects are actually too big to fit in the frame, which is why I always have the trusty old 100mm on hand for a quick changeover.

Despite its little personality quirks, the MP-E 65mm macro lens is a pleasure to use and I am extremely happy with the results it has provided so far. At AUD$1,200 it wasn’t cheap, but it has proven its worth in my opinion.

Do you have a question or comment? You’re welcome to get in touch with me through the CONTACT PAGE.